Corey S. Pressman is a teacher, writer, and artist residing outside Portland, Oregon. He has published academic works, stories, and poetry. Corey teaches in the Public Health and Wellness program at University of Portland and is a long-standing Fellow of Arizona State University's Center for Science and the Imagination. He recently published The Double-Edged Sword: An Evidence-Informed Workbook for the Well-Being of Nurses and the Places They Work with the American Nursing Association. He is currently working on A Rewilded Mind: An Evidence-Informed Guide to Reclaiming Your Wild Imagination with Arizona State university.

A post by Corey S. Pressman

How might we arrive at a distinctive definition of the human animal? Taxonomy leaves little on the table. Clearly, it is not our spines, hands, bipedalism, or brainstems that define us. In the end, what puts the sapiens in Homo sapiens is essentially cortical. Our species benefits from a variety of neurological novelties such as phonemic speech, self awareness, and neuroplasticity.

And also this about the human brain: imagination lives here. Like so many other taxonomic gifts, imagination itself is ancient. But while other species may have rudimentary forms of imagination, human imagination gets up to all kinds of species-specific shenanigans. Culture, science, art, stories, selves: all of these belong to the human imagination, as does anxiety, society, and the cultural habits that contribute to climatic and economic dissonance.

However, the soaring possibilities offered by human imagination are balanced by another amazing neurological feature: automaticity. Automaticity refers to the process by which certain tasks or behaviors become so well-learned and practiced that they can be performed without conscious effort or attention. In the context of the brain and behavior, automaticity refers to the ability to carry out tasks efficiently and effectively with minimal conscious awareness or cognitive resources. When a behavior becomes automatic, it is executed quickly and effortlessly, often without the need for deliberate decision-making or conscious monitoring. This phenomenon is facilitated by the brain's ability to form neural pathways and consolidate learning through repetition and practice.

Automaticity plays a significant role in everyday life, allowing individuals to perform routine tasks, such as walking, driving, or typing, with little conscious effort, thereby freeing up cognitive resources for more complex or novel activities. However, automaticity can also lead to errors or biases when applied inappropriately to situations that require careful attention or conscious control. If left to its own devices, this amazing reflex may also lead to a life devoid of creativity, agency, and possibility.

As an artist, writer, and teacher, my central life question is this: how might we balance automaticity’s yang and imagination’s yin? Being, well, automatic, automaticity has a head start (pun intended). But I contend that we can hack our habit-forming capacity by building new habits of imagination.

My contention is that the imagination is always at work. However, it is rarely engaged with awareness and autonomy. In day-to-day existence, we are always imagining, yet rarely creative. Something powerful may be gained from unraveling this paradox. My recent work with the Arizona State University Center for Science and the Imagination is dedicated to explaining ways we might gain the skill of volitional imagining so as to realize new futures. At University of Portland, I frame this as a public health issue. Surrly, one’s capacity for volitional imagination is a measure of psychological and subjective well-being.

A metaphor I’ve been working with is “domesticated vs. wild.” In this arrangement, I propose we view our automatized imaginations as domesticated, while our volitional imagination as “wild.” Inside this handy trope, I advocate for rewilding the imagination. But let’s start with first things first.

What is Imagining?

Imagination is something brains do. Human brains in particular are very good at imagining. So much so, it is safe to say that one of the things that makes us human (as opposed to chimps or cats) is our huge mental capacity for imagination. Imagination is central to much of the human experience, including the very human activities of:

Culture

Language

Learning

Creativity

Hope

Empathy

This neurological endowment has a shadow as well. Imagination is associated with dysfunctions such as body dysmorphia, anxiety, and paranoia. These maladies of the imagination point to its role in maintaining a sense of self, of reality, and of safety.

There are many ways to define imagination. But whether you are considering it from the vantage of the humanities, neurology, psychology, or philosophy, there are some common elements. For the purposes of this post, let’s focus on these commonalities and define imagination as…

…experiencing or considering phenomena that are not present to the senses.

Thusly defined, imagining is central to the activities that comprise much of one’s mental interiority. Thinking happens in the imagination. So do memories, dreams, fantasies and creations. In this way, you are your imagination. But you are not alone.

Who shapes your imagination?

Our capacity for imagination is present at birth. Given its centrality to the human experience, it is no surprise that imagining may be seen as an instinctual cognitive feature, like the deep drives for food and affection. Infant minds reach out into the “blooming buzzing confusion” of unstructured experience and begin to make sense of the world. The resulting patterns of experience and expression are our first imaginings. But these cannot form without direction and reinforcement from our caretakers.

A newborn’s developing imagination is influenced and educated in large part by her social environment. Her imagination is guided to recognize as real the rules, mores, and patterns of the world that caretakers reinforce. As she develops, she inherits a dynamic set of expectations and assumptions—the whole of her psychosociocultural “reality.” Through her lifespan, this reality is continually formed and maintained in the imagination with the active and passive participation of those around her. This process is called different things by different disciplines. An anthropologist may call this enculturation or habitus, a psychoanalyst may refer this as the imaginary and the real, a sociologist may cite cultural hegemony, a philosopher may talk about ideology or the spectacle.

Imagination Domestic and Wild

It’s amazing how effortlessly and seamlessly this occurs. The alphabet you are reading at this moment is objectively a collection of patterned squiggles. But our capacity for shared imagination transforms this into a rich communication system full of nuance and possibility. Literacy is a years-long project of deep learning and imagination--so deep as to be unforgettable. The alphabet is objectively nonsense, but we experience it as involuntarily real. Nothing short of organic brain damage can get you to forget how to read. Much of our expectations and assumptions about the world operate this way. When was the last time you forgot how to speak, or sit at a table and eat, or drive? It would be catastrophic if the imaginary rules that support these behaviors were as forgettable as a phone number.

Let’s call this busy and impressive dimension of your imagination the domestic imagination. The domestic imagination keeps and breathes realness into your acquired ideas, beliefs, and assumptions. This is what allows you to participate in society and culture while developing and maintaining a sense of self. The domestic imagination establishes a more-or-less sensible and predictable daily experience of the world. Because of this, you do not have culture shock every time you wake up.

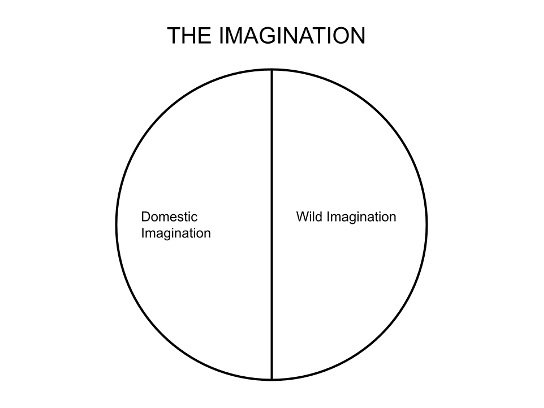

Given its sociocultural content, the domestic imagination focuses on shared realities—on creating sameness. In common parlance, however, we consider imagination as the source of creativity, of human achievements such as philosophy, art, and innovation—on achieving newness. Let’s call this newness aspect of the imagination the wild imagination. The wild imagination, when set free to do its thing, is capable of astonishing achievements. It is the source of all that is new in our human world. The wild imagination is where we discover new connections, achieve novel understanding, create art and architecture, stories and songs.

On the whole, our imagination is central to both what is considered “normal” and the manifestation of what is new.

Rewilding Your Imagination

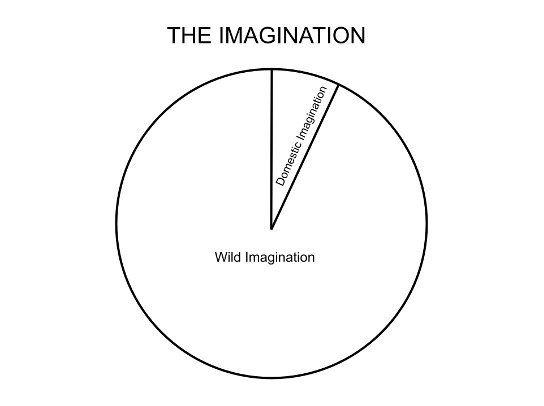

Imagine a state in which one’s imagination was lacking balance. For example, the domestic imagination could be quite dominant, like this:

Here, one is well-established in the normal and largely “programmed” by the shared domesticated imagination. A dominant domestic imagination makes for predictable followers of normative cultural and subcultural prerogatives and ways of being. At the same time, the minimization of the wild imagination allows for less creative expression, less critical consideration of the normative, less innovation—less newness. Psychologists may describe this state as a sort of fixedness.

There could also be an arrangement in which the wild imagination is outsized, like this:

The culture in which I am situated often labels this arrangement as some sort of malady. It is considered madness to possess so little consensual imagination. Even novelty and creative expression must be anchored in the context of shared imaginings to be properly communicated and integrated. But, as they say, yesterday’s noise is today’s music. In the words of William Blake, a wild imaginer par excellence, “What is now proved was once only imagined” (2011). However, the tolerance and cultivation of such marginal hyper-creative personalities requires cultural apparati and an open-mindedness uncommon in the domesticated imaginings of our normative day-to-day.

For this reason, my work on rewilding the imagination (and my workbook in progress) is not a guide to being a mad genius per se. Rather, I am to set out a framework for achieving balance by expanding your wild imagination, by rewilding your imagination. The exact ratios are up to you. Maybe it looks like this:

Or perhaps more like this:

Go as deep up into the wild as you dare. According to the iconoclast psychologist R.D. Laing, “Madness need not be all breakdown. It may also be a breakthrough. It is potentially liberation and renewal...” (1990).

Rewilding your imagination is a skill. And as such, it can be learned. We possess the ability to cultivate our wild imaginations and question the cultural realism that views “the way things are” as inevitable and immutable. It is often said that our current calamities of climate and civility represent a “crisis of imagination.” We may now have the language to be more precise: perhaps we are experiencing a crisis of 1) a maladaptive domestic imagination and 2) a wild imagination on too short a leash. If we are to transform this age-old “crisis of imagination,” we must consciously manipulate our personal domestic/wild ratio and rewild the mind.

As indicated by the wildness metaphor, it is our assumption that the wild imagination is as instinctual and intrinsic as the domesticated imagination. The skill is not in the imagining per se, but rather in creating the conditions for the wild imagination to do its thing. Creativity is latent in you; the skill is in removing barriers and setting it loose.

I encourage you to lengthen the leash, reevaluate the real, and experience the sort of creativity your mind evolved to achieve. Let’s at least try.

References:

Laing, R. D. (Ronald D. (1990). The politics of experience ; and, the bird of paradise. Penguin.

Blake, W., & Phillips, M. (2011). The marriage of heaven and hell. Bodleian Library.