Michael Omoge is a PhD candidate at the University of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa, and his research interests intersect modal epistemology, philosophy of mind, and cognitive science. He can’t stop visualizing the sheer depth of Europa’s ocean and the different sorts of exotic life form that might be inhabiting it.

A post by Michael Omoge.

Recently, imagination has been getting increased philosophical attention on account of its relevance in explaining a host of things, such as mindreading, creativity, autism, pretense, modal epistemology, and so on. Central to this attention is the cognitive architecture of imagination. The thought is that understanding the cognitive architecture of imagination will illuminate the range of functions that have been attributed to imagination. Hence, Schellenberg notes, “gaining a better understanding of the cognitive architecture of imagination is of interest not just to philosophy of mind, but also to aesthetics and to modal epistemology” (2013: 498). Experts mostly agree, but with exceptions, that imagination has its own dedicated system, which constitutes this architecture. That is, according to some experts, imagination has an internal structure, such that experiential and propositional imagination can be explained in terms of perceptual and language systems sending input into this internal structure, respectively. According to others, imagination doesn’t have any internal structure, in that experiential and propositional imagination come for free with our perceptual and linguistic capabilities, respectively.[i]

I think by taking lessons from aphantasia seriously, it will become clear that neuroscientific evidence regarding the interdependence between perception and language supports only the view that imagination has an architecture. And there is much benefit to be had by making this sort of adjudication. For instance, if the functions that have been attributed to imagination are to be illuminated by a better understanding of imagination’s cognitive architecture, then that presupposes that imagination has an architecture to begin with. In addition, if imagination does have an architecture, then we can apply what we know about cognitive modules/systems á la Jerry Fodor and others to such an architecture, thereby giving a naturalistic account of imaginative justification.[ii] So, what lessons from aphantasia should we take seriously?

Aphantasia is a condition where one does not possess a functioning “mind’s eye” and typically can’t voluntarily visualize imageries. Aphantasia can be partial, i.e., involving one or more sense modalities, or complete, i.e., involving all sense modalities. I will continue in terms of complete aphantasia here. In complete aphantasia, experiential imagination is completely lost, but propositional imagination remains fully functional. For example, some who has complete aphantasia will be unable to imagine the sound of his car but will be able to imagine that ‘his car is making a sound’. As Watkins (2018) notes, his complete aphantasia, which makes him unable to visualize thought experiments and mentally time travel during complex mathematical calculations, hasn’t in any way made him terrible at theoretical physics. His propositional imagination suffices for both the thought experimentation and the complex mathematical calculations that are involved therein.

This shows that there is a sort of asymmetry in how experiential and propositional imagination are interrelated. Experiential imagination may depend on propositional imagination, but propositional imagination need not depend on experiential imagination. As we’ve seen, all cases where experiential imagination is fully or partially functioning are cases where propositional imagination is fully functioning. But not all cases where propositional imagination is fully functioning are cases where experiential imagination is fully or partially functioning. Experiential imagination seems to be irrelevant to propositional imagination, but propositional imagination seems to be very much relevant to experiential imagination.[iii] If so, then a view of imagination’s cognitive architecture that’s much closer to the truth should be able to accommodate this asymmetry without contravening neuroscientific evidence about the interdependence between perception and language. As things turn out, only the view that imagination has an architecture can; the view that imagination lacks an architecture can’t. But first, what neuroscientific evidence?

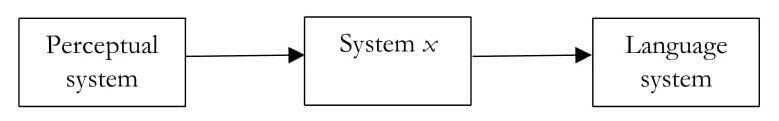

It is that even though perception and language are interdependent, they are not directly related. To put it in boxology terms, there are no direct connections, by way of arrows, between perceptual and language systems. Consequently, neuroscientists and cognitive scientists explain the interdependence between perception and language via a third system to eschew any sort of direct connection between them. For instance, Aziz-Zadeh et al. (2006) explain it through action systems, Mitterer et al. (2009) through memory systems, Landau et al. (2010) through face recognition systems, Heurley et al. (2012) through decision-making about colours, and so on. Representing this third system as ‘system x’, below is a rough depiction of the interdependence between perceptual and language systems:

This way of explaining the interdependence between perceptual and language systems corroborates some epistemological conclusions about perception. For instance, it is standard that perceptual beliefs are basic beliefs. But this will be false if perceptual systems are directly connected to the language system, for such direct connection would imply that perceptual systems are inferentially non-opaque, where a cognitive module/system is inferentially opaque if its doxastic outputs are not the result of an introspectible train of reasoning (Lyons 2009). Since the language system is inherently inferential, in that what we say have already been subjected to some form of reasoning process, any direct connection between perceptual and language systems, would make perceptual beliefs to also be the result of a reasoning process, which they aren’t. They are rather cognitively spontaneous, and that’s why they are basic beliefs. If so, then it’ll be epistemologically pernicious if perceptual systems are directly connected to the language system. But that is precisely what the view that says imagination lacks an architecture relies on to explain the asymmetry in the relationship between experiential and propositional imagination.

Since according to the first view, imagination has an internal structure of its own, we can simply say that, in aphantasics, perceptual systems are malfunctioning, and, so, they aren’t sending inputs into imagination’s internal structure, but the language system is fully functioning, and, so, it is sending input into the internal structure. Hence, the lack of experiential imagination and the preservation of propositional imagination in aphantasia. Experiential imagination is irrelevant to propositional imagination because only the language system is sending inputs into imagination’s internal structure. Propositional imagination is relevant to experiential imagination because both perceptual and language systems are sending inputs into imagination’s internal structure. The architecture of imagination is serving as the third system in terms of which the interdependence between perception and language is explained. No direct connection between perceptual and language systems is invoked. Everyone is happy. Not so with the second view.

According to it, imagination has no internal structure of its own, so there’s no third system in terms of which we can explain the interdependence between perception and language. We are forced, then, to explain the asymmetry in the relationship between experiential and propositional imagination in terms of a direct connection between perceptual and language systems. In aphantasia, experiential imagination is lost because of damage to perceptual systems, and propositional imagination is preserved because of normal operations in the language system. Experiential imagination is irrelevant to propositional imagination because perceptual systems are malfunctioning, so, they aren’t cooperating with the language system. Propositional imagination is relevant to experiential imagination because both perceptual and language systems are fully functioning, and, so, they are cooperating with each other.

While this analysis, unlike the first view’s, doesn’t populate our mental architecture, it clearly contravenes the above adumbrated neuroscientific evidence about how perception and language are interdependent. Worse still, the analysis implies that perceptual beliefs aren’t basic beliefs. And even if we aren’t better placed to adjudicate between the two views on the basis of neuroscientific evidence, perhaps because neuroscience is still developing and it might turn out that perceptual and language systems are indeed directly connected after all, we can adjudicate between them on the basis of the basicality of perceptual beliefs. Certainly, if any of our beliefs are basic, perceptual beliefs are. Thus, the view that entails the non-basicality of perceptual beliefs should be adjudged to be further away from the truth about the cognitive architecture of imagination than the one that entails the basicality of perceptual beliefs. If so, then for now at least, it is theoretically more useful to say that imagination has, in one way or another, a cognitive architecture. In which case, we can be rest assured that such architecture will indeed foster the range of functions that have attributed to imagination.

[i] This classification isn’t a fine one. Some theorists only talk about imagination and belief, and some others, only imagination and desire. That is, some deny that imagination has an internal structure relative only to belief, and some deny the same relative only to desire. To complicate the matter, some countenance an internal structure for imagination relative to belief, but not relative to desire, and vice-versa. For more on this classification, see Lao and Doggett (2014).

[ii] Lyons (2009) does similar thing for perceptual justification vis-á-vis perceptual systems.

[iii] The first conclusion is standard: everyone seems to agree that propositional imagination is non-experiential. The second conclusion isn’t so standard: most theorists would say experiential imagination is non-propositional, but see, for example, Joanna Ahlberg’s contribution to this blog for why experiential imagination seems to be propositional.

References:

Aziz-Zadeh, L., Wilson, S. M., Rizzolatti, G., and Iacoboni, M. (2006). Congruent embodied Representations for Visually Presented Actions and Linguistic Phrases. Current Biology 16: 1818–23.

Huerley, L. P., Milhau, A., Chesnoy-Servanin, G., Ferrier, L., Brouillet, T, and Brouillet, D. (2012). Influence of Language on Colour Perception: A Simulationist Explanation. Biolinguistics 6(3-4): 354–82.

Landau, A. N., Aziz-Zadeh, L., and Ivry, R. B. (2010). The Influence of Language on Perception: Listening to Sentences about Faces Affects the Perception of Faces. The Journal of Neuroscience 30(45): 15254–61.

Liao, S., and Doggett, T. (2014). The Imagination Box. The Journal of Philosophy 111(5): 259-275.

Lyons, J. (2009). Perception and Basic Beliefs. Oxford: Oxford UP.

Mitterer, H., Horschig, J. M., Müsseler, J., and Majid, A. (2009). The Influence of Memory on Perception: It’s Not What Things Look Like, it’s What you Call Them. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning Memory and Cognition 35: 1557–62.

Schellenberg, S. (2013). Belief and Desire in Imagination and Immersion. The Journal of Philosophy 109(9): 497-517.

Watkins N. W. (2018). (A)phantasia and Severely Deficient Autobiographical Memory: Scientific and Personal Perspectives. Cortex 105: 41–52.