A conference report by Serena Gregorio

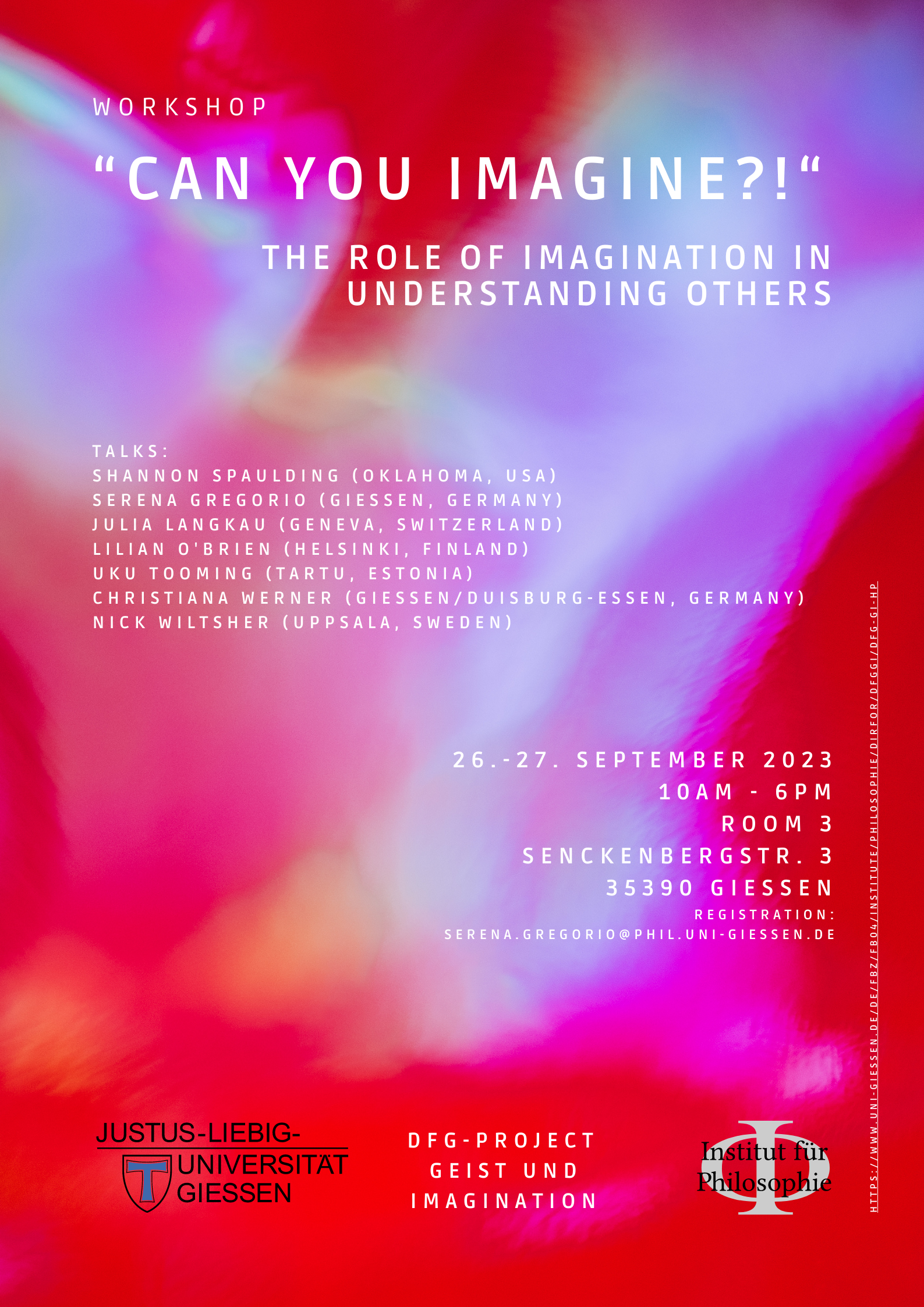

It is a truism in our everyday thinking that interpersonal understanding is valuable. But what does it mean, exactly, to understand someone? This question drove the workshop “Can you imagine?!” The Role of Imagination in Understanding Others, held on September 26th and 27th, 2023 at the Justus Liebig Universität Giessen, as part of the DFG-funded research project Geist und Imagination. The guiding assumption was twofold: Understanding someone cannot be reduced to, nor exhaustively explained by, acquiring propositional knowledge of their mental states and rationalizing explanations of their actions in terms of causes. Simultaneously, the act of imaginatively re-enacting another person's perspective in a phenomenally rich way seems to be a promising approach to making sense of at least some cases of other-directed understanding. I’ll briefly summarize the talks by highlighting three main themes that emerged.

Serena Gregorio is a PhD student and research associate (wissenschaftliche Mitarbeiterin) in the DFG-project Geist und Imagination at the Institute of Philosophy of the Justus-Liebig-Universität Gießen, Germany.

The first theme could be framed as an inquiry into successful cases of understanding another person. Lilian O'Brien's (University of Helsinki, Finland) talk provides a good starting point. She engaged with the workshop's guiding assumptions and further inquired about the role experiential states might play in understanding other persons. She began by criticizing Donald Davidson's (1963) account of causal explanations of actions as being third-personal and objective. One reason this account falls short is that our practical thinking is often experiential, meaning that experiential states matter for grasping accurately practical reasons (e.g. how good a soup is) and evaluating options. Most people seem to be aware of this: when searching for an answer to “why did S do A?”, we often put it as “what does S see in A?”, and to answer we simulate others' practical deliberation processes while taking into account experiential states. One way to integrate them into the simulation is by directly inspecting the phenomenal features of an object; for example, one can re-taste a soup that one dislikes, in order to understand why someone might order it. However, this is often not possible, and we resort to experiential imagination. O’Brien distinguished between an egocentric and a non-egocentric perspective when evaluating experiential states as reasons for action. In the former, we wonder if something is a reason for us; in the latter, we wonder if something is a reason for them. This is reflected in how we imagine: in the non-egocentric perspective, we sometimes need to imaginatively adapt relevant dispositions that the target person has, which might differ from our own.

Christiana Werner (Duisburg-Essen/JLU Giessen University, Germany, and a Junkyarder) focused on what O'Brien called the egocentric perspective, which she refers to as “Imagine-Self”. She proposed an answer to the question: what does it mean to successfully understand someone? According to her, we can understand someone’s actions, decisions, or mental states if we can imagine ourselves as ourselves in their situation, and act, decide, or react in the same (or similar) way. Werner does justice to an everyday intuition and a common practice: we easily reach for this kind of mental enterprise, simulating ourselves in their place, which is cognitively less costly than imagining being themselves. She underscores this by noting that when we share relevant features with the target person, such as character traits, social background, etc., our experiential imaginings come about effortlessly, along with a “feeling of concordance” with the other person. When we don’t share such features, we can adjust our imagined self to resemble the other person, but this proves challenging with experiential (as opposed to propositional) imagining. This gap in relevant features and dispositions, and the greater effort required to bridge it, might explain at least some cases of imaginative resistance.

Other talks chose a different approach, focusing not on success cases, but rather on instances of unsuccessful understanding. Julia Langkau (University of Geneva, Switzerland, also a Junkyarder) challenged Olivia Bailey’s empathy account (2022), which requires that the emotional reaction the target person shows, and that the empathizer tries to simulate, also seems appropriate to the empathizer. Langkau considers a particularly challenging case of “empathic perspective-taking”, in which we try (a) to experientially imagine ourselves as the other person in order to grasp their emotional reaction to a given circumstance; and (b) we do not share relevant emotional dispositions and character traits with the other person. According to Bailey, because of (b) it is a hopeless endeavor to simulate the emotional reaction. Langkau rejects this conclusion as too pessimistic and criticizes (b) as too demanding. Her strategy is to question a strong and schematic conception of “sensibility”, Bailey's term for patterns of emotional dispositions. She rejected two ways of understanding sensibilities: as generic traits, they are not very informative or useful for the challenging case she's dealing with; as idiosyncratic, they are too individual to be simulated. Assuming a skill-based understanding of experiential imagination, she proposed that sensibilities can be considered, as I would put it, imaginatively plastic. When we struggle to develop an imagining in which we simulate another person's emotional reaction to a given object, one way to address this challenge is to shift our imaginative attention to the lower-level salient features of the object and work our way up from there. She concludes that these cases of imaginative resistance should not be considered as hopeless as they might initially appear.

I engaged with an argument that Michael Cholbi (2023) recently put forward as an answer to why so-called psychopaths cannot grieve. My aim was to work out the role of experiential imagination for what might be called, very loosely, self-understanding, and which is implicit in the text. Even if the focus was on self-directed understanding, the idea was to show that, at least according to Cholbi, self- and other-directed understanding are more interrelated that what one might assume. Briefly, this is what I take Cholbi to say with respect to the imagination: evidence shows that psychopaths have impaired imagination; this affects their ability to mentally travel in time (MTT) and access their past and future selves in a meaningful, affectively charged way. MTT is a crucial mental ability for developing a cross-temporal prudential relationship with oneself, which is necessary to commit to what Christine Korsgaard calls practical identities (roles that we invest in, identify with, and act upon, such as mother, colleague, union member, etc.). Practical identities entail obligations and prohibitions and provide the framework for our meaningful relationships with others. Cholbi contends that psychopaths cannot form meaningful relationships because they lack practical identities; since grief is a response to losing a meaningful relationship, psychopaths have nothing to grieve for. Among the problems I have with this proposal, the following is worth mentioning: Cholbi owes us at least a clarification of the relationship between the impairment of imagination and the impairment in the capacity of feeling and recognizing affective states, which is another characteristic impairment of severe personality disorders, particularly of the antisocial kind (“psychopaths”); it might well be that the difficulty in MTT, which is, in their case, devoid of affect, fails because there is a general difficulty in accessing affects, and not the other way around.

A way to frame the remaining three talks of the workshop is to view them as explorations of the social dimension of the issue of other-directed understanding. In different ways, they engaged with the idea that understanding others happens within some sort of relationship framework, and that this is relevant to our understanding of that very same mental process or action. Shannon Spaulding (Oklahoma State University, USA) delved into the social aspect of successful/unsuccessful cases of empathy as simulative perspective-taking. She drew attention to philosophical arguments (e.g. Prinz 2011), as well as empirical evidence supporting the skepticism toward the reliability and, therefore, epistemic utility of empathy. It seems clear that we do misunderstand others quite often. Spaulding sought ways to explain patterns of success and failure. Assuming that imagination is a skill, the quality of the result depends, among other things, on how good we are, and how much effort we make, especially in challenging cases. Spaulding suggests that our motivation in engaging with empathic understanding is one aspect of a complex explanation that accounts for patterns of success and failure, because motivation explains the effort we put into the imagining. In cases where we experience negative affects, where we risk social capital (an example could be empathizing with violent criminals), where imaginative perspective-taking might interfere with our goals, or when imagining turns out to be cognitively costly (for instance in terms of time), then we tend to be less motivated to engage in imaginative perspective-taking. On the contrary, when we experience positive affects, exhibit socially desirable traits, and, most importantly, when we perceive meaningful common ground with the other person (for instance when we belong to the same social group, e.g. political party), then we’re inclined to make a greater effort. This idea complements nicely a similar point made by Werner and Langkau: imaginative perspective-taking comes more or less easily, depending upon whether we share relevant personality features with the other person (such as character traits, affective dispositions, or even material conditions like age, gender, country of origin, political affiliation, etc).

Uku Tooming (University of Tartu, Estonia; also a Junkyarder) expanded his research into the role imagination plays in understanding desires by “scaling up” his inquiry: he considered collective desires, and took architecture as a representative instance of an object of a collective desire. The problem he addressed concerned how a group of people can improve their collective desire in a rational way. After introducing the standards for the rational evaluation of individual desires, such as feasibility, goodness, and expected satisfaction of a given object of desire, he proceeded to apply them to architecture as an exemplary case of collective desires. Architectural practices can be seen as processes in which architects develop “collective imaginings”. These imaginings involve a group of people sharing an imaginary object, mutual awareness of others' mental states relevant to the imagining, and coordinated intentions. Others' contributions to refining the object of the collective desire, for instance an imagined building, become particularly prominent when the architects' expertise in the imagined domains complements each other. This is especially relevant in the context of participatory design, where imagined users often test the functions of spaces and their features, offering a way to refine and correct them.

Finally, Nick Wiltsher (Uppsala University, Sweden, also a Junkyarder) tested some ideas pertaining to his own account of understanding and the role of imagination within it. He started by establishing a contemporary, even if admittedly artificial, general account of understanding. According to it, understanding constitutes an epistemic achievement primarily involving data processing, and resulting in a true representational state. In a similar vein, understanding others amounts to data gathering and processing, wherein the other, as I would put it, functions as a data repository. Wiltsher argued that this doesn’t capture the dynamics of interpersonal understanding accurately; he proposed framing it as a reciprocal, collaborative, and open-ended activity, making a connection between this and his conception of imagination. In his "process view", imagination shouldn't be regarded as a distinct state defined by its belief-likeness or perception-likeness; rather, its attributes are best characterized as elements of a process, wherein states act as inputs and outputs. Wiltsher laid the foundation for an exploration of how imagination, as a process, contributes to the meaningful dimension of loving relationships, which he terms understanding. Although I did not present the talks in chronological order, Wiltsher was, indeed, the final speaker. This was opportune due to the experimental nature of his ideas, fostering a collaborative endeavor in which several participants proposed alternative terms for "understanding," thereby illuminating the various facets of the process he touched upon.

The discussion continued into the evening at the Schiffenberger Kloster, but alas, I do not have the space to summarize it here. I can only say that it was enjoyable, even in the absence of Federweißer wine (a seasonal specialty in Hessen!).

In conclusion, I would like to extend my personal thanks to all the guests, as well as to my research group colleagues, Gerson Reuter, Matthias Vogel, and Christiana Werner. It takes two to tango, and many more to ensure the success of an event of this nature.

References

Bailey, Olivia (2022). Empathy and the Value of Humane Understanding. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research 104 (1):50-65.

Cholbi, Michael (2023). Empathy and Psychopaths’ Inability to Grieve. Philosophy 98 (4):413-431.

Davidson, Donald (1963). Actions, Reasons, and Causes. Journal of Philosophy 60 (23):685-700.

Prinz, Jesse (2011). Against Empathy. The Southern Journal of Philosophy 49: 214–33.