Sara Arjomand is a junior at Claremont McKenna College studying philosophy. She had to memorize “Jabberwocky” in the sixth grade, and she’s glad that nine years later it has finally proved useful.

A post by Sara Arjomand

Lewis Carroll’s “Jabberwocky” is a nonsense poem. Carroll begins:

“’Twas brillig, and the slithy toves

Did gyre and gimble in the wabe:

All mimsy were the borogoves,

And the mome raths outgrabe” (Carroll 1900).

Half of the words in the first stanza of “Jabberwocky” are made–up. None of us can say what “slithy toves” refers to, or what it means for these “slithy toves” to “gyre” and “gimble.” Despite Carroll’s use of gibberish, though, it seems that we’re able to imagine what’s happening. That’s strange. How are we able to imagine what we can’t understand? That’s the puzzle I’ll be interested in, here—the puzzle of the apparent imaginability of nonsense. Let’s try to solve it.

First, let’s confirm that “Jabberwocky” is, in fact, nonsensical. We’re preempting the obvious objection, here, that somehow “Jabberwocky” does make sense—that there isn’t any puzzle, at all. To see why the objection fails, let’s take a look at Carroll’s gibberish terms. Unlike real words, which possess established meanings, Carroll’s made–up words don’t refer to anything “out there,” or pick out anything in particular. To what, for example, does “ice” refer? Frozen water. What does “brillig” refer to, though? Can you restate “brillig” with any precision? No. There’s a genuine absence of meaning in “Jabberwocky,” then—and it’s this which precludes our understanding of the poem.

Let’s return to the puzzle of imagination. Even lacking understanding, there’s still a great deal that listeners and readers are able to do with nonsense. As Cora Diamond once observed, when engaging with nonsense, we “[go] as far as [we] can with the idea that there is [a proposition]” expressed by it (Diamond 2000). And the suggestion, here, is that we can go quite far, indeed. Even though nonsense doesn’t itself make sense, or “mean,” it can often be made sense of, by us. [1] We’re susceptible to Adrian Moore’s so–called “illusions of sense”; our minds tend to see or create sense, even where there isn’t any (Moore 2003). How do these illusions arise? Via non–arbitrary mental associations. There are four types, which may occur in combination:

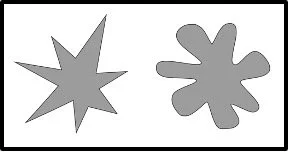

1. Sound symbolism: Take, for example, the Bouba–kiki effect (Gómez Milán 2013). In studies conducted worldwide, participants tended to associate the nonsense word “kiki” with spikier shapes (left), and “bouba” with rounder shapes (right). Words—and especially gibberish terms—often evoke specific imagery, and call concepts to mind.

2. Resemblances: We might attempt to make sense of gibberish terms via their similarities to other, real words—for example, by connecting “brillig” to “brilliant” and “gyre” to “gyrate.”

3. Syntax and Semantics: In a sentence, the arrangement of words indicates each word’s part of speech, which partially determines semantic function. For example, in “Jabberwocky,” which follows English syntax, “slithy toves” is of the form [adjective] [noun]. (“Jabberwocky” contains the occasional real word—often a preposition or article—which establishes typical sentential structure).

4. Expectations: Our dealings with fictional nonsense are informed by an appreciation of genre conventions. We view the gibberish of “Jabberwocky” in light of Carroll’s tendency to write fantasy. As a result, our illusions of sense aren’t constrained by the physics of our reality—we’re free to let the “borogoves” defy gravity, for example.

We need not be aware that these four factors influence our attitudes toward nonsense. Though the language of “making sense” might seem to suggest a deliberate effort, in reality the process occurs with near-automaticity. These four explanations offer an account of what our pattern-seeking minds do, often unconsciously, to produce illusions of sense.

Associations are the key to illusions of sense; and illusions of sense are, in turn, the key to the relationship between imagination and nonsense. Let’s now attempt to make that relationship more precise. Here’s the claim: although we can’t have imaginings of nonsense, we can have imaginative responses to nonsense. To see the distinction in action, we’ll first examine a non-nonsense example. [2]

Consider the invitation to imagine John Green, the YA author and Youtuber. In all likelihood, you’ve just called to mind an image—it’s probably of a white, middle–aged male with glasses; he’s got a “bookish” look about him. That’s an imagining of John Green—John Green is a person, and you’ve imagined him.

An imagining of John Green.

There’s a great deal of debate in the imagination literature about how an imagining gets to be an imagining of some thing in particular. What exactly did you have to do to imagine John Green? And what makes it the case that you’ve imagined John, rather than Hank—his brother—or John’s zombie twin, for example? But let’s set aside that question for now. What matters is that we’ve got an idea of what you ought to be aiming at—something person–y, and vaguely John Green–y. [3]

An imaginative response to “John Green”

Now, consider an imaginative response to the statement “Imagine John Green.” Suppose that you’re unfamiliar with the novelist. When you hear the instruction to imagine John Green, a different image might come to mind—maybe, of the color green. In this case, you haven’t imagined John Green himself—you haven’t imagined the person—but you’ve certainly had an imaginative response to the prompt, and it’s not entirely arbitrary either. You didn’t imagine yellow, or blue, or red—you imagined green.

Let’s apply this distinction to nonsense. Let’s say that you’re told to imagine Carroll’s “slithy toves.” What would an imagining of slithy toves be? In my view, there’s just no such thing—“slithy toves,” unlike “John Green,” doesn’t refer to anything. There’s no imaginative target, nothing to aim at. Nothing, that is, except for your associations with “slithy toves.”

Accordingly, you’re able to have an imaginative response to the prompt. Maybe when you hear “slithy toves,” you imagine slimy toads. Of course, though, a slimy toad isn’t a slithy tove. When you try to imagine slithy toves—or any other gibberish expression—you’re doing something closer to the second John Green example. There, you imagined the color, and not the person; here, you imagine your associations—your illusion of sense—and not the thing itself. And there’s no other option, because there is no “thing itself” when it comes to nonsense.

Now that we’ve seen what these imaginative responses are like, we might want to ask: can we evaluate their appropriateness? We said that if you weren’t imagining something person-y, you probably weren’t imagining John Green. Is there an equivalent sense of legitimacy or correctness when it comes to imagining via our associations? Or, are there an infinite number of acceptable ways to respond to nonsense?

In my view, that’s not the case. Just as non-nonsense utterances prescribe imaginings of, nonsense utterances invite imaginative responses, and not just any response to those invitations will do. [4] Even if the invitation doesn’t lock in a particular target, there’s reason to believe that what we’re being invited to have, here, isn’t just any experience at all, but rather a kind of experience.

To see why, let’s think back to “Jabberwocky.” We said that one way you might respond to “slithy toves” would be by imagining slimy toads. But, there might be other responses you could have which would be well-suited to the piece, too. For example, an imagining of a slithering snake. Or maybe, of a slippery eel.

What about a squeaky balloon animal? Intuitively, there’s something inappropriate about this last imagining. Why?

When you read the first stanza of “Jabberwocky,” the answer is apparent. Carroll is trying to stir up a particular feeling—a sense of foreboding, something to get the hairs on the back of your neck to stand up. And balloon animals aren’t foreboding. They’re the sort of thing you’d find at a children’s birthday party. If you’re imagining balloon animals, in other words, you’ve failed to accept Carroll’s invitation.

Think about it this way: if a reader is free to “do” anything in response to “Jabberwocky,” how can we say that the piece possesses anything in the way of aesthetic value? If art in the vein of “Jabberwocky” is supposed to move us, it must move us in particular directions. There must be better and worse—more and less legitimate—ways of approximating the kinds of experiences offered by “Jabberwocky,” and instances of nonsense like it.

While there’s certainly more to be said on the topic, we’ve just attempted an examination of the puzzle of the apparent imaginability of nonsense—that is, of our seeming ability to imagine what we’re unable to understand. If our discussion has been correct, illusions of sense, which trigger imaginative responses distinct from imaginings of, have helped us to solve it. And, as we’ve noted, not just “anything goes” for these imaginative responses. English teachers get this last point best of all—not every literary interpretation of “Jabberwocky” (begrudgingly submitted by a disinterested middle schooler) will earn an “A.”

Notes

[1] Oza and Bogucki separately develop “pretense theories” of nonsense; the two theories, though not identical, have in common the Diamond-esque suggestion that we enter into the seeing of nonsense as sense. For both, the relevant mechanism is the following prescribed pretense: each expression—linguistic item, or “prop”—must possess semantic value. The twin concepts developed here—illusions of sense and making sense of—borrow from the notion of semantic pretense. Neither Oza nor Bogucki explicates how, in great detail, our pretending is supposed to proceed, however; what exactly are we doing? The four non–arbitrary mental associations detailed earlier attempt to close the explanatory gap. See Oza (forthcoming) and Bogucki (2023).

[2] The John Green example is inspired by and adapted from Cora Diamond’s “Mr. Green” example, in Diamond (2000).

[3] The discussion makes use of the notion of imaginative “targets” or “aims.” For more, see Kind (2016) and Kind (2024).

[4] Walton famously argues that fictional pieces prescribe imaginings. In my view, literary nonsense (“Jabberwocky” is one example) invites imaginings. Though distinct from the “thicker” notion of a prescription or mandate, the discussion of imaginative invitations borrows from Walton’s basic formulation. See Walton (1990).

References

Bogucki, K. (2023). The Riddle of Understanding Nonsense. Organon F: Medzinárodný Časopis Pre Analytickú Filozofiu, 30(4), 372–411.

Carroll, L. (1900). Through the Looking-Glass and What Alice Found There. Chicago: W.B. Conkey Co.

Diamond, C. (2000). Ethics, Imagination and The Method of Wittgenstein's Tractatus. In Alice Crary & Rupert J. Read (eds.), The New Wittgenstein, 149-173. New York: Routledge.

Gómez Milán, E., et al. (2013). The Kiki-Bouba Effect: A Case of Personification and Ideaesthesia. Journal of Consciousness Studies, 20(1–2), 84–102.

Kind, A. (2016). The Snowman’s Imagination. American Philosophical Quarterly, 53(4), 341–348.

Kind, A. (2024). Accuracy in Imagining. Philosophy and the Mind Sciences, 5.

Moore, A.W. (2003). Ineffability and Nonsense. Aristotelian Society Supplementary Volume, 77, 169-223.

Oza, M. (forthcoming). Nonsense: A User's Guide. Inquiry: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Philosophy.

Walton, K. (1990). Mimesis as Make-Believe: On the Foundations of the Representational Arts. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.