Nele Van de Mosselaer is Assistant Professor of Philosophy at Tilburg University. Her research focuses on the role imagination plays in our interactions with virtual objects.

A post by Nele Van de Mosselaer

Imagine the following situation: you open a door in a videogame. An in-game alert pops up with the message “Congratulations, you opened the door!” Immediately afterwards, the game – being apparently philosophically inclined – puts that message into question. A new pop-up alert clarifies that it is not really you, the player, who opened the door, but rather the player-character. Moreover, no door was opened. Rather, the action that took place was an input of a certain command on a controlling device. Someone moved the mouse around and clicked a button. Lastly, there was not even an actual door involved in this interaction, but merely a group of pixels, a computer-generated digital entity that is meant to evoke a door in your imagination. So, the game argues, you did not really open a door, did you? Would it not be more precise to say that you, taking on the role of the protagonist of this game, used your cursor to interact with a virtual model and thus fictionally opened a door that is represented to exist in the gameworld?

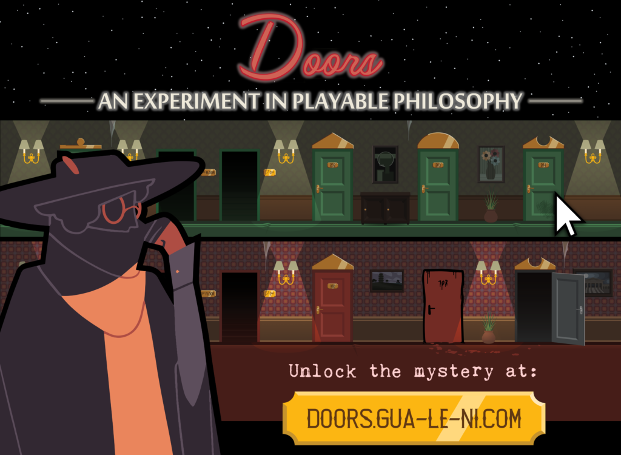

The playful interaction described here might seem silly, frustrating, or even a tad bit pedantic. But it is part of the game I co-designed with Prof. Stefano Gualeni from the Institute of Digital Games in Malta. We created Doors, a free, experimental point-and-click browser-game. I would like to make use of this blogpost to tell you a bit more about why we did this.

The idea originated at a conference dinner, where I somewhat lazily summarized my position by saying that, surely, objects in videogames are fictional. “That’s not true, though, is it?” a game scholar seated opposite me responded. “Take, for example, a door in a videogame. There is nothing fictional about such a door: it is a simulated door that actually exists on your computer. You can see it, as it is there on your screen. You can open it, close it, maybe even lock and unlock it. You don’t need to imagine anything, you just interact with it.”

As soon as I heard the word “door,” my heart sank. I knew what was being referenced here, as it had been used against me so many times: Espen Aarseth’s paper “Doors and Perception: Fiction vs Simulation in Games” (2007). In this paper, Aarseth writes that two kinds of doors can be found in videogames. Only some are fictional. These are just non-interactive background elements, which players cannot interact with, similar to doors in movies or paintings (2007, 42). And others are virtual doors, as they simulate the behavior of actual doors within the given gameworld (ibid.). As expected, the game scholar then went on to summarize David Chalmers’ defense of virtual realism (2017): objects in digital games, such as doors, genuinely exist as data structures upheld by computers. There is thus no need whatsoever to qualify them as fictional.

I replied to this scholar with Waltonian-inspired virtual irrealism (see also Wildman and McDonnell 2019): of course there is an actually existing computer-generated object, but this object is not a door. It’s merely a prop that mandates the imagining of a door. Similarly, the actions we perform on computer-generated objects are props: clicking on the representation of the door, for example, allows us to imagine that we are opening the door.

These words fell on deaf (or unwilling) ears. My inability to convince this person of the fictionality of in-game objects and actions still bothered me hours later when I went to bed. And then, like so often, when sleep was already overdue, it hit me what I should have done. I should have given counterexamples of hypothetical door-encounters in videogames that could call into question Aarseth and Chalmers’ views on interactivity, fictionality, and virtuality.

What if, for example, a videogame filled with functioning doors would feature one door that players could not interact with at all? That would be funny: as players stumbled upon this door, they would likely assume it was interactive and they could open it by approaching it and clicking on it. In fact, only by trying to interact with it, they would be able to find out that it was non-interactive. But then they would have demonstrated that this door, despite arguably being non-interactive, was different from any door we see in a movie, right? After all, they would not even try to interact with a movie door.

Or what if there was a door that was just painted on a wall within the videogame? Such a door would truly be part of the background, in a different way than the non-interactive door would be, right?

At this point, it was 2AM and I was giggling to myself: imagine that, when players tried to interact with this painting of a door in the game, they would get a pop-up message saying “Ceci n’est pas une door”. I was thinking, of course, of René Magritte’s painting The Treachery of Images. This work nicely experientially discloses how representation works. By means of the sentence “Ceci n’est pas une pipe” (this is not a pipe) written under the painterly representation of a pipe, Magritte prompts his audience to take a step back, and look at the work for what it ultimately is: paint on a canvas. In an interview with Claude Vial, Magritte said: “The famous pipe. How people reproached me for it! And yet, could you stuff my pipe? No, it's just a representation, is it not? So if I had written on my picture ‘This is a pipe’, I'd have been lying!” (Magritte 1979, 642).

Of course, Magritte was right. But what if we represented that same pipe virtually, as a computer-generated, interactive 3D-model? In-game, you could hold it, stuff it, and smoke it. Would that virtual pipe be more of a pipe than Magritte's painted one? And if so, in what sense?

Doors and pipes were merging together in my feverish thoughts. My hypothetical game could work like Magritte’s conceptual artwork did: it would be a self-reflexive representational work that would make a point about the nature of representation by materially instantiating it, offering its audience a “personal first-hand experience” of it (Schellekens 2007, 86). With that thought, I finally found sleep.

Together with Prof. Gualeni, who had experience developing videogames with philosophical themes and aspirations, I eventually actualized my fever dream. We designed Doors to stimulate players to reflect on the characteristics of virtually represented objects. The game took the shape of a playable essay that interactively confronts players with questions about the representations of eleven in-game doors.

As mentioned before, Doors is a silly game. It’s silly not only in the sense that it is intended to be short and humorous, but also because it invites questions that are very similar to what philosophers of fiction would call “silly questions” (see Walton 1990, 176). Such questions call attention to problems or apparent contradictions within represented content, but they are not to be taken seriously when appreciating this content. They are “pointless, inappropriate, and out of order” and appreciators are unlikely to even notice the inconsistencies these questions are about (ibid.). Indeed, players of digital games are usually not concerned with the fact that they are interacting with pixels, that a glitch or malfunction makes the game narrative nonsensical, or that they are unable to set in-game doors on fire even though they are represented as being made out of wood. When immersed in games, these questions seem inappropriate and distracting. In Doors, however, these questions are deliberately “outmersive” (i.e. they purposely reduce in-game immersion, see Kubiński 2014). They are explicitly and self-reflexively foregrounded as part of the game experience. Through whimsical, weird, and even frustrating situations, Doors is meant to help players adopt a detached, critical view on their interactions with in-game representations (Gualeni 2016).

Presenting Doors through this blogpost text is somewhat self-defeating: the game itself was motivated by our belief that there are insights and intuitions that cannot be suitably communicated in ways that are exclusively linguistic, but should be experienced instead. Doors might not give any clear answers, but I do hope people find value in the questions it raises experientially. It can be used as an educational tool, to motivate discussion and reflection on the ontology of virtual objects, the role imagination plays when we are navigating virtual environments, the nature of immersion and interactivity, and, on a meta-level, the potential of videogames as philosophical thought experiments.

Doors can be played for free (which takes about 20 minutes) on www.doors.gua-le-ni.com.

References

Aarseth, E. (2007). “Doors and Perception: Fiction vs. Simulation in Games.” Intermediality: History and Theory of the Arts, Literature and Technologies, 9: 35–44.

Chalmers, David J. (2017). “The Virtual and the Real.” Disputatio, 9(46), 309–352.

Gualeni, S. (2016). “Self-reflexive videogames: Observations and corollaries on virtual worlds as philosophical artifacts.” GAME – Games as Art, Media, Entertainment, 5(1).

Kubiński, P. (2014). “Immersion vs. Emersive Effects in Videogames.” In Stobbart, D. and Evans, M. (Eds.), Play, Theory, and Practice: Engaging with Videogames. Oxford, UK: Inter-Disciplinary Press, 133–141.

Magritte, R. (1979). Écrits complets. André Blavier (Ed.). Paris, France: Flammarion.

Schellekens, E. (2007). “The Aesthetic Value of Ideas.” In Goldie, P. & Schellekens, E. (Eds.), Philosophy and Conceptual Art. Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press, 71–91.

Wildman, N. & McDonnell, N. (2019). “Virtual Reality: Digital or Fictional?” Disputatio, 11(55), 371–397.

Walton, K. L. (1990). Mimesis as Make-Believe: On the Foundations of the Representational Arts. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.