Niklas Maranca, a visual artist, scenic painter, and lecturer, is currently a doctoral candidate at the Berlin University of the Arts. His research focuses on the application of artistic image composition concepts to imaginative processes, with particular attention to introspection and its influence on creative thinking.

A post by Niklas Maranca

Insight into the structure and approach of a practice-based PhD project on imagination

This text traces a path from practice to research. It opens with three short scenes from my own artistic work—pantomime, still life drawing, and scenic painting. Each captures a concrete moment of making, observed through first-person inquiry.

These scenes serve as a starting point: they give rise to questions about the trainability of imagination and its role as a skill. The second part presents imagination games—practical, experimental formats developed to investigate such questions. The closing section situates this method within the broader frame of my doctoral research and offers a glimpse of a first prototype of the approach.

Pantomime

I imagine an invisible wall. I am very close to it. If I stretch out my arm, I might be able to touch it. Slowly and carefully, I raise my hand and turn the palm forward. I spread my fingers so they form a flat surface. Just before I touch the wall, I slow the movement, as if the air were becoming denser. With wide eyes, I fix my gaze at the invisible wall—filled with expectation. Now my hand makes contact. I have found the wall.

Still Life Drawing

On a table lie small objects of various kinds. I shift, arrange, and reconfigure them until they form a balanced composition. Again and again, I return to the exact spot from which I intend to draw. Then I light the objects, walk around them with the lamp, and compose the shadows. Once I have found a motif, I begin to draw. In doing so, I explore the surfaces of the objects with my eyes. Suddenly, observing a texture brings back something else in memory. Spontaneously, images and scenes arise—especially those involving tactile sensations. Drawing the still life becomes a process of remembering.

Scenic Painting

In front of me stands a wooden box made of boards, slats, glue, and nails. I work on it so that it looks as though it were made of marble. I prime the wood, fill in small cracks, and sand the surface. Using various brushes and sponges, I apply colored layers, create textures and patterns, and draw veins into the wet paint. At each stage, I ask myself how the painted surface could become more similar to the imagined material. A dialogue develops between the painted image and my mental images of marble. I paint every side, layer by layer, until the wooden box resembles a polished marble block. If the illusion succeeds, the box looks heavy and cool. For a brief moment, I believe I am looking at real stone.

* * *

These scenes illustrate that imaginative processes are not disembodied abstractions. Rather, they are entangled with perception, memory, movement, and interaction with the environment. In each case, creative action is guided by an active engagement with mental imagery. I ask myself questions such as:

What does the wall I attempt to touch feel like? Is it warm or cold, smooth or rough? What sound would the piece of wood I am drawing make if I ran my finger over it? How heavy would it be to move a large block of marble?

Questions like these evoke mental imagery and make it available for further shaping. In this sense, imaginative processes function as internal rehearsals that enable artists to find ways to bring about the desired impression or object.

While it is self-evident that artistic work requires skill and practice, it is less obvious that imagination itself can be developed in the same way. Yet this is precisely what my project explores. Following Amy Kind’s view that imagination can be understood and cultivated as a skill (Kind 2020), I treat imaginative acts as intentional, repeatable, and learnable.

Imagination Games

The question, then, is how such imaginative processes can be practiced, observed, and investigated in a structured yet experiential way? My response is to develop imagination games – practical formats that integrate perception, imagination, and reflection.

The concept of a "game" in this context is not tied to rules, goals, or competition. Rather, it refers to a framed setting in which participants are invited to do something – to engage in an activity that is open-ended and experiential. The games provide a structure for making certain experiences possible, not for achieving a specific outcome. It is this shift from goal to process that makes the format especially productive for the investigation of imagination.

In seminars on creativity techniques with design students, I began developing the initial idea for these formats by combining experiential exercises with interdisciplinary texts on imagination. In these exercises—such as visualizing colors and textures, pantomime, walking meditations, or brief episodes of sensory or perceptual deprivation—students documented their experiences through writing and body maps. These maps consist of printed body silhouettes on which students draw the locations and qualities of felt sensations.

The pedagogical approach draws on phenomenological principles: participants are invited to describe their experiences as closely as possible, without immediate interpretation. Inspired by Claire Petitmengin’s second-person methodology (Petitmengin 2006), I use open-ended prompts that support verbal articulation of subjective experience. In the group discussions that follow, students often describe their own imaginative processes—how imagery arises, shifts, fades, or intensifies. These conversations reveal not only the diversity of imaginative experience, but also certain patterns of language and metaphor.

Many students, for example, use terminology from visual composition to describe their mental imagery:

"When I imagine the object standing still in front of me, it is very hard to see it clearly. There is always a black/transparent filter over the center of the image. (It becomes clearer toward the edges.) The more senses I involve, the clearer the imagination becomes."

"The object seemed to emerge from the darkness piece by piece. The space or room surrounding it was still entirely obscured by shadow. The imagined areas of the object were gradually illuminated, one after another."

These reflections suggest a metaphorical framing: imagination is described as if it was an act of seeing, illuminating, or composing. Aspects such as contrast, depth, sharpness, and framing are applied to mental content. This echoes the theory of conceptual metaphor developed by Lakoff and Johnson (Lakoff and Johnson 2003), according to which abstract domains are structured through metaphorical mappings from more concrete domains—often visual and spatial ones.

One of my research goals is to analyze these texts and drawings to examine whether they reveal a consistent conceptual mapping: one that treats imagination as image-making. This metaphorical transfer allows for new questions to emerge:

How can imaginative processes be illuminated? How does one shift perspective within them? What kinds of spatial or temporal framings exist in mental imagery?

The imagination games use such questions as prompts for further exercises. They are not designed to provide definitive answers but to create conditions in which such questions can be explored experientially. In this way, the games become a method for making abstract concepts tangible.

Fig. 1

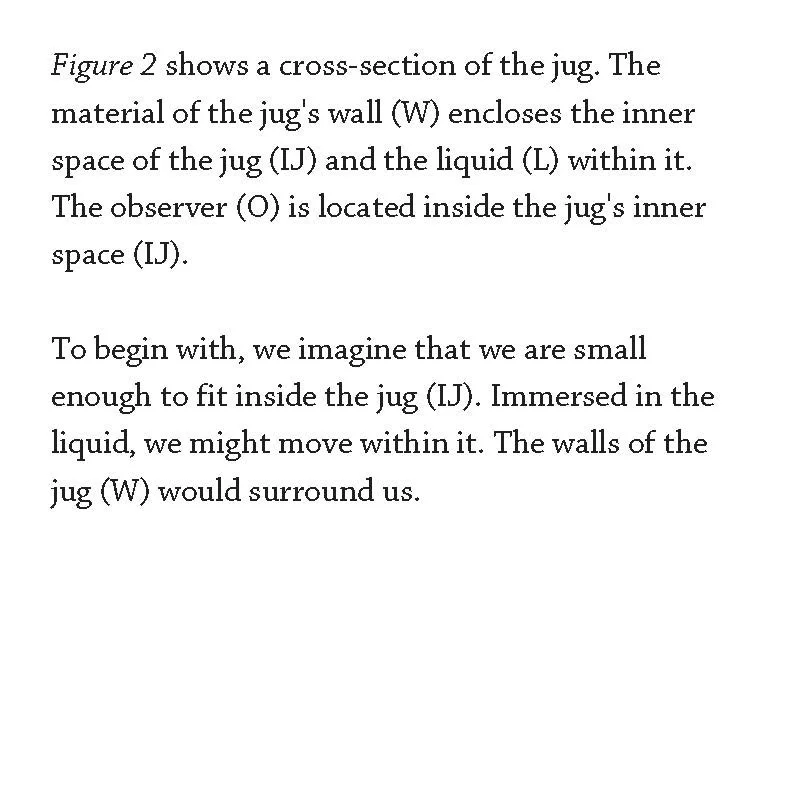

Fig. 2

Each game consists of short textual instructions accompanied by schematic illustrations. The instructions borrow patterns from hypnotherapeutic language—not in terms of inducing trance, but in their use of suggestion, ambiguity, and indirect prompts (see Fig. 1). The illustrations, in contrast, are schematic and refer to scientific or technical styles of drawing (see Fig. 2). This contrast between text and image is intentional: it aims to stimulate associations while leaving space for interpretation. The excerpt from the prototype below demonstrates how such a game functions. It invites the reader to imagine a simple object from different perspectives and to observe changes in texture and scale. This opens a space where imagination can be experienced as both plastic and intentional. (For more details, see the Prototype available here.)

Looking Ahead

This article outlines the structure and approach of my doctoral project at the Berlin University of the Arts, developed under the supervision of Prof. Dr. Stephan Porombka. The project, currently titled Imagination Games: Experiments in Designing Imaginative Processes, explores how imagination can be investigated through practice-based methods. The seminars that led to this research were conducted at Burg Giebichenstein University of Art and Design in Halle.

Through formats like this, imagination becomes not just an object of inquiry but a method of inquiry. My hope is that this approach can inform not only art education, but also other fields where imagination plays a central role: design, psychology, philosophy, pedagogy.

At this stage of the project, I welcome feedback, suggestions, and critical perspectives that might help shape the next phases of development.

References

Kind, Amy. 2020. “The Skill of Imagination.” In The Routledge Handbook of Philosophy of Skill and Expertise, edited by Ellen Fridland and Carlotta Pavese, 335–346. New York: Routledge.

Lakoff, George, and Mark Johnson. 2003. Metaphors We Live By. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Petitmengin, Claire. 2006. “Describing One’s Subjective Experience in the Second Person: An Interview Method for the Science of Consciousness.” Phenomenology and the Cognitive Sciences 5 (3–4): 229–269.