Lucia Oliveri is Assistant Professor in Theoretical Philosophy at the University of Münster. Her research focuses on the role of imagination in cognition from the perspective of the history of Western philosophical thought.

A post by Lucia Oliveri

Imagine a world destroyed by a thirty-year-long war, the most devastating war that seventeenth-century Europe had ever seen. Imagine standing in front of a destroyed land, like Germany. You would likely want to understand how such an evil could have happened and educate people in order to prevent it from ever happening again.

From this perspective, some early modern thinkers, such as G.W. Leibniz (1646–1716), viewed philosophy as a way to improve education, and, consequently, individual and social well-being. They imagined a school where students would learn through play. “One can teach also serious matters through play. And in this context, teaching is more effective,” writes Leibniz in order to challenge those who think that play is just frivolous entertainment (Aufzeichnungen nach einer Lektüre von »ZUFÄLLIGEN GEDANCKEN« [ca. 1691.] A IV 4 608). Quite the contrary: play is a reason-oriented, pleasant, imaginative activity because the mind is at ease with itself. In the free joy of play, human beings develop their theoretical and social skills, their rationality and moral attitudes, and they acquire the status of being responsible citizens. And they do so much better than by being subjected to the hard and long memorization of abstract notions.

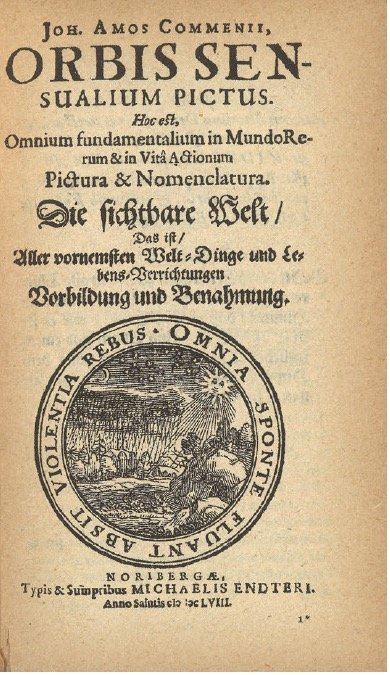

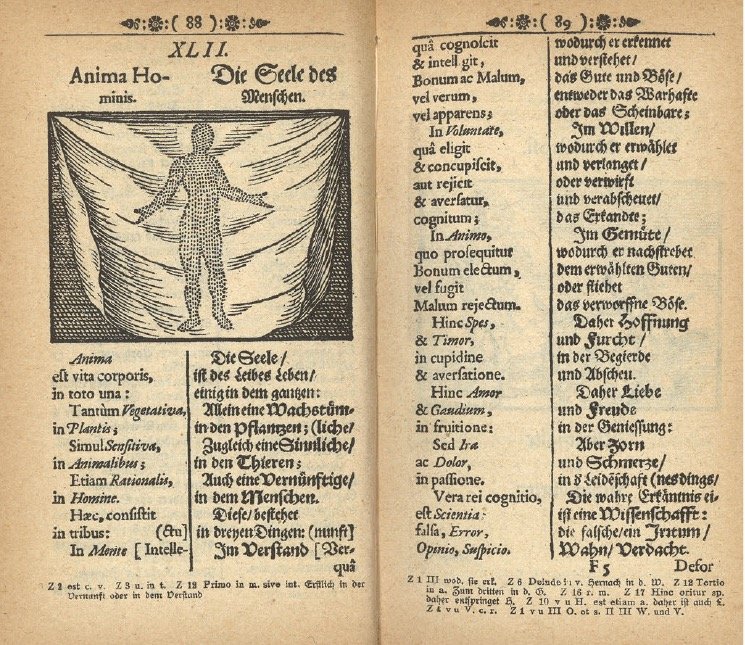

Leibniz’s ideas were greatly influenced by the work of Johann Amos Comenius (1592–1670), who thinks that learning becomes more effective when it happens in joyful contexts, such as play. In his pedagogical works, Comenius criticizes Scholastic teaching methodology because it is based on memorizing notions without comprehending them. This lack of understanding in learning prevents students from applying what they have learned in concrete life-situations. The main pedagogical message realized in his revolutionary book “The Sensible World in Pictures” (1658, Orbis sensualium pictus; see Fig. 1 and Fig. 2)—which was not a philosophical treatise but the first illustrated encyclopedia for children—is that joyful learning puts students in a state of mind that facilitates the assimilation of knowledge. In play, students learn by doing via imaginative situations. The pleasure imparted by learning through play is a gentler way of teaching that does not force notions into the mind of students, and school is not perceived as painful.

Fig. 1: The frontispiece of Johann Amos Comenius’s Orbis sensualium pictus, with the motto: “Omnia sponte fluant absit violentia rerum” (“let everything flow spontaneously, let violence be absent from things”).

Leibniz and Comenius thus promote an idea that also shapes pedagogy today. Empirical studies show a correlation between play—characterized as an actively engaging, joyful, iterative, meaningful, socially interactive activity—and children’s development of holistic skills—defined as emotional, social, physical, cognitive, creative abilities (for an overview, see Parker, Thomsen, and Berry 2022). Appealing to ideas that contemporary studies trace back to the Russian psychologist Lev Vygotsky (1896–1834)—who argues for the interrelation between play, creativity, the imagination, and inner speech—literature on children’s early education shows that play is relevant to the exercise of a child’s imagination (Fleer 2011 and 2018, Tsai 2012 for a review of the literature; most recently, Nilsson, Ferholt, and Lecussay 2018). What contemporary debates lack—and what the philosophical debate concerning the imagination has to offer—is an answer to the question of why it is the imagination that makes it possible for play to contribute to the development of holistic skills. I outline here what I take to be Comenius’s and Leibniz’s answer to this question.

Fig 2: Figures 2 and 3 shows four pages of Comenius's Orbis sensualium pictus ([1658] 1910), which was published in both German and Latin as an easier way for children to learn both languages. Each picture is first commented on in Latin, followed by the German translation. The first picture shows a teacher inviting a student to learn. The second picture shows the soul as a representation of the body. Through these images, the teacher explains to the student what the soul is.

To understand the centrality of the imagination in learning through play, one first needs to recall the faculty psychology that thinkers of the early modern period thought was constitutive of the human mind. Faculties are nothing but abilities of the mind that implement the execution of tasks devoted to practical and theoretical achievements—from obtaining what one desires to acquiring knowledge about abstract matters. Since tasks differ greatly, so do the relevant abilities that—alone or in cooperation with others—contribute to the execution of those tasks. Abilities are divided into those that are lower and higher; the lower being those that are closer to sensory representations, and the higher being those of reason, representing things in the abstract such as kinds (what is common to all things of the same kind), essences (what makes a thing that very thing), and notions that cannot be represented by means of the senses, like the notions proper to morals (such as justice and good) or metaphysics (such as substance or being). The imagination is located between the lower and the higher abilities, and the will completes the picture as the conative ability to determine the mind to action.

Fig 3: See description with Figure 2.

Working within this psychological framework, Comenius argues that the teaching methodology of the Scholastic tradition is ineffective because it engages higher abilities without involving lower ones. This separation prevents theoretical learning from becoming effective because it remains abstract and cannot be applied to concrete, life-related situations (Comenius [1658] 1910: Preface, p. 1). To provide an example, it would be as if I wanted to teach someone what a tomato is without providing any information about its sensible constitution and then expecting students to recognize a tomato in a garden. As a result of the disconnect between concrete life situations, where the student knows what a tomato is and what to do with it, and theoretical life, where the student learns about the tomato in the abstract, theoretical knowledge is deemed superficial, far-fetched, and useless. This discourages students from learning or, even if they do learn, encourages them to quickly forget what they have learned (Comenius [1658] 1910: Preface, p. 2).

When students learn through play, on the other hand, they learn through problem-focused and emotion-focused situations to relate abstract knowledge (like rules) to concrete situations. Students connect the abstract to the concrete, thus they learn the value of abstract reasoning when planning actions, anticipating the consequences of their actions, and adapting what they know to new situations. As play-situations are often socially interactive, when learning through play students learn to include their peers’ points of view in their actions. Learning through play is effective because it teaches reasoning skills through concrete experiences that motivate action through imagination. By coping with concrete situations through reason-oriented imagination (play), the will acquires habits for responding to situations in life, even outside the playfield. Play is not just an effective way to teach serious matters; it is the most effective way because it engages the subject holistically. Both sensory and motor skills are implemented through reasoning, and action guarantees the involvement of the will in executing practices.

Comenius’s and Leibniz’s pedagogical ideal hinges on an understanding of the imagination that does not fit into the taxonomies that we use nowadays, especially those of the sensory and cognitive imagination. The task of the imagination is not exhausted by the recreation of mental states that are like perceptions. Sensory input is supplied by images as a prompt. Images prompt the imagination to operate on sensible data and transform them into examples and symbols. When sensory representations are used to exhibit rules, kinds, or essences, the imagination makes the abstract relatable to real-life by informing theoretical and moral practices through concrete examples. However, this process is not the same as make-believe (van Leeuwen, 2013).

The process of imagining involves two types of transformation: one from the concrete to the abstract, which makes intellectual knowledge possible, and the other from the simple to the complex, which expands and adapts knowledge to new, complex situations. This ability to abstract and expand requires sensory imagination because reason uses the imagination's manipulation of data as a guide. Reason is put into practice when attempting to find concrete solutions by applying simpler or more abstract models to explain concrete cases. Since transformation requires active participation, the will is modified by the acquisition of habits. Once outside the playfield, the will is naturally incentivized to adapt those habits to new situations, thereby improving the subject’s creative skills. Play is not just pleasure and distraction. Play is how humans exercise their ingenuity because they explore their abilities, learn their limits, and develop further skills.

According to the Leibniz-Comenius tradition, learning through play is effective both because it teaches students how to relate to and use what they learn, as well as improves their capacity to adapt to new situations. The imagination is central to the success of learning through play. While play has been a paradigmatic human activity in scholarly attempts to understand the imagination (Walton 1990, and most recently Ferrarin forthcoming), the specific phenomenon of learning through play is absent from philosophical treatments of the imagination. Philosophical treatments are likewise absent from the debate on education, play, and the imagination. Can the Leibniz-Comenius tradition encourage scholarly exchange on common questions, such as the definition of play, of creative and holistic skills, and most of all, of what the imagination contributes to learning through play? The answer to this last question promises to be especially fruitful insofar we learn about the imagination by thinking through the way in which play enables effective learning, thereby providing a qualitative answer to why we humans (and perhaps non-humans as well) learn better through play.

References

Leibniz, G.W. 1923. Sämtliche Schriften und Briefe, ed. Preußische Akademie der Wissenschaften, Berlin and Boston: de Gruyter.

Comenius, Johann Amos. [1658] 1910. Orbis sensualium pictus, ed. by Julius Klinkhardt, Leipzig, reprented in: Johannes Kühnel - Uwe Sandfuchs (2014), Johann Amos Comenius, Orbis sensualium pictus. Faksimile der von Johannes Kühnel besorgten und 1910 bei Julius Klinkhardt in Leipzig erschienenen Ausgabe. Bad Heilbrunn: Verlag Julius Klinkhardt.

Ferrarin, Alfredo. Forthcoming 2025. A World Not of this World. The Reality of Images and Imagination. New York: Bloomsbury Publishing.

Fleer, Merilyn (2011). ‘“Conceptual Play”: Foregrounding Imagination and Cognition during Concept Formation in Early Years Education.’ Contemporary Issues in Early Childhood, 12(3), 224-240.

Fleer, Merilyn. 2018. ‘Conceptual Playworlds: the role of imagination in play and learning.’ Early Years, 41(4), 353–364.

Nilsson, Monica, Ferholt, Beth, & Lecusay, Robert. 2018. ‘“The playing-exploring child”: Reconceptualizing the relationship between play and learning in early childhood education.’ Contemporary Issues in Early Childhood, 19(3): 231-245.

Parker Rachel, Thomsen, Bo Stjerne, and Berry Amy. 2022. ‘Learning Through Play at School – A Framework for Policy and Practice.’ Frontiers in Education Vol. 7 DOI=10.3389/feduc.2022.751801

Tsai, Kuan Chen. 2012. ‘Play, Imagination, and Creativity: A Brief Literature Review.’ Journal of Education and Learning 1 (2): 15-20.

Van Leeuwen, Neil. (2013) ‘The meanings of “imagine” Part One: constructive imagination.” Philosophy Compass 8 (3): 220–230.

Vygotsky, Lev S. 1967. ‘Play and its Role in the Mental Development of the Child.’ Soviet Psychology 5 (3): 6-18.

Vygotsky, Lev S. 1990. ‘Imagination and Creativity in Childhood.’ Soviet Psychology, 28(1), 84–96.

Walton, Kentall L. 1990. Mimesis as Make-Believe. On the Foundations of the Representational Arts. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.